One of the main contentions of this newsletter is that the rise of tutoring over the last few decades has been driven by parental disaffection with educational institutions, both public and private. There is no greater source of disaffection than grading, which occupies a central place in a student’s life and carries enormous consequences, both for psychological-emotional health and for college admission.

At the heart of grading practices lies a central question: “What is merit?” Is it knowing the right answer, or is it exerting maximal effort? Is it getting to the end result first or fastest, or improving slowly over time? Is it playing along with the classroom bureaucracy (nightly homework, deadlines, group work, etc.), or wowing with an amazing final exam?

Two recent news items have addressed controversies in grading practices.

Traditional grading is decentralized and without a single standard

In “Every Teacher Grades Differently, Which Isn’t Fair,” published on March 16, 2023 in The Conversation, an online independent media outlet, education professor Laura Link highlights that there is no single, accepted way of grading. Teacher training programs don’t spend as much time on grading practices as they do on curriculum and classroom instruction.[1] The result is that every math (or English or history…) teacher creates her own grading policies, which might benefit or disadvantage a particular student.

Math, theoretically, is based on hard numbers, but even math teachers can skew final results if, for example, they drop the lowest quiz grade, or allow students to hand in homework late without a penalty, or let students retake tests, or offer opportunities to earn extra credit. English teachers may work hard to remain even-handed and unbiased when grading student essays, but what is a B+ paper for one teacher, may be an A for another. It’s inherently subjective.

It is common practice (at least at the college level) to curve the results of math and science tests. But curving masks the “real” results of a particular assessment because it adjusts grades to create an even distribution of grades across the A-F spectrum, even if those grades may be undeserved. For example, if a teacher makes a test too hard, and most scores end up in the 70s, a teacher may curve the scores upward, so more students end up with grades in the 80s or 90s. There’s no reason why the results need to be evenly distributed from A to F, though perhaps the practice adds fairness if a teacher has misjudged the level of difficulty of the test. I suppose it is also psychologically pleasing to see a broader spectrum of results, which also helps to differentiate students in the class.

Link’s research indicates that diverse grading practices do not only present questions of fairness; they can also harm students: “The effort to keep up with multiple teachers’ different grading expectations causes students chronic anxiety and stress, especially for those students with poor organizational, time-management and self-regulation skills.” In other words, beyond the demands of learning new content, students find it difficult and stressful to figure out what the different metrics for success are and how they might fulfill them.

Link reports that parents who feel disadvantaged by a teacher or school’s grading practices aren’t standing for it. They’re suing, arguing that a lower than anticipated or unjustly awarded grade may cost their child academic honors, scholarships, and even admission to selective colleges.

I would add that less litigious (but no less concerned) parents aren’t hiring lawyers; they’re hiring tutors, who, beyond possessing specialized knowledge of various subjects, are also able to explain grading rubrics and metrics to students who haven’t encountered them before. Tutors help students reinforce those weighted components of the final grade that play to their strengths, while encouraging them to seize every opportunity to run up the score (asking for extensions, retaking quizzes, doing work for extra credit, etc.).

Some tutors may even know the student’s teachers personally from having been in their class or from tutoring students who took the class in years past. Using inside knowledge, the tutor can explain what constitutes merit in that particular class and can direct the student to play the grading game in ways that optimize the outcome.

But, beyond unfairness and anxiety, there may be something further disquieting about grades: systemic bias.

“Equitable Grading” offers many chances at mastery and puts the emphasis on final tests

Enter the “Equitable Grading” reform movement, which has been catching on in school districts in California, Iowa, Nevada, and Virginia. The leader of this movement is Joe Feldman, author of Grading for Equity, who, like Link, has expressed dissatisfaction with “inconsistencies” that crop up across different subjects and teachers.[2]

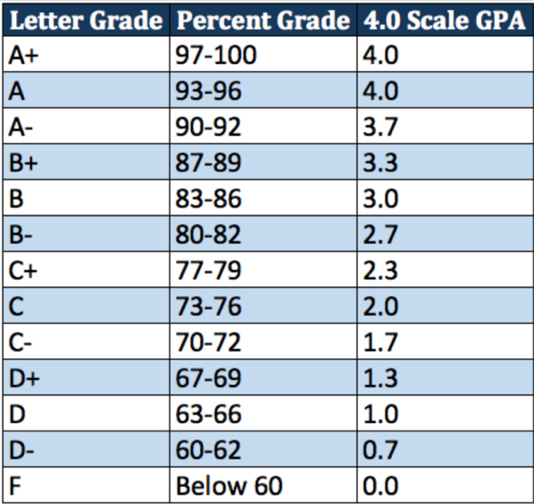

Feldman argues that all teachers adopt a 0-4 grading scale. This is the pervasive method at the college level, instead of the 0-100 scale that most high schools use. As you can see from the chart below[3], the 4.0 scale GPA is fairer because it links a letter grade value to all outcomes above 0, giving the student credit for any amount of correct answers. By contrast, the 0-100 scale essentially eliminates 60 points of correct answers by giving the student no credit for them and assigning an F. For example, if a student answered 50% of the questions on her math test correctly, she would get an F on a 0-100 scale, but a C on a 0-4 scale.

Feldman’s suggestion is excellent. Using the 0-4 scale and standardizing it across the country will provide both fairness and clarity when colleges compare students from different high schools. Instead of evaluating students by different mathematical standards, a single standard would ensure that colleges are making as informed a decision as possible when they look at student grades. But beyond tweaking the mathematical logic behind grading, the equitable grading movement also proposes other changes to the way students are graded.

On April 26, 2023, Sara Randazzo of the Wall Street Journal explained the movement’s main ideas:[6]

Instead of being held to “arbitrary deadlines” for homework submission, students are given more leeway to hand in finished work without penalty.

Students who don’t perform well on a particular test are given further chances to demonstrate their knowledge of the material.

Students are not graded on their behavior, including classroom attendance and participation.

Feldman’s system allows students to demonstrate mastery of the material by the end of the semester without penalty for missing deadlines or making mistakes along the way. As Feldman expresses it, equity in grading eliminates the “traditional idea that we average a student’s performance over time.”[4] This way, grading reflects, in numerical terms, the “growth mindset” educators want students to adopt because the final grade would reflect only the high point of achievement (theoretically the result of struggling and overcoming mistakes along the way).[5]

Why is there a need for these changes? Traditional grading methods may be biased toward students with more stable home lives or who come from privileged backgrounds. For students who face disruption at home, or who have learning differences, or who work a job after school and aren’t always in control of their schedules, there are now more opportunities to perform well.

In practice, equitable grading assigns less weight to softer skills, such as in-class participation and homework practice, and more weight to “summative assessments” that test whether the knowledge has been successfully learned—no matter how or when.

And what is the result of the change in grading practices so far? Randazzo writes, “A prepandemic study by Crescendo Group [an organization founded by Feldman] showed a decrease in Ds and Fs under the equitable grading—and also a decrease in the number of As awarded.” In other words, more final grades end up in the middle, as Bs and Cs. The system creates more equity, but it doesn’t lead to much excellence, nor does it help differentiate students. In practice, it seems to be doing the opposite of curving; it leads to “clumping.”

While I’m against bias of all kinds and am in favor of equitable practices, innovation within schools, and responsiveness to the needs of the populations in various school districts, I am apprehensive of what equitable grading proposes. It seeks to keep “behavior” out of a student’s final grade, but I think it may actually lead to unforeseen changes in student behavior.

For one thing, when attendance isn’t compulsory, or when students are allowed to skip class without penalty (even for legitimate reasons), it weakens the sense of class community and affects the collaboration and cross-pollination within the classroom. If being present with one’s peers is no longer required, what will happen to the togetherness of the classroom dynamic? Beyond the distraction of empty chairs, what happens if the classmate with whom a student is presenting a group project simply fails to show up? If classroom time doesn’t count, I can imagine a cynical student saying to himself, “Why bother coming?”

In addition, equitable grading puts too much power in the hands of teenagers, who, at least in my experience, must be guided through the process of learning by engaging with the daily and nightly repetition that builds skills, knowledge, organization, communication, and time management. These are not innate human qualities; they are inculcated through practice and repetition, the modeling of behaviors by parents, teachers, or tutors, and by personalized engagement with one’s work. There is a clear difference between ability and account-ability.

Perhaps equitable grading works well at the college level, when students have theoretically reached a certain degree of maturity and independence, but high schoolers need more guardrails. Not all students have “intrinsic motivation,” which the equitable grading movement offers as one of its principles. I do note that, according to Feldman, students in equitable grading classrooms continued to do homework even if it was ungraded and that there was less stress in the classroom because students felt comfortable taking risks knowing they wouldn’t be penalized for mistakes. If that’s true and can be replicated in more classrooms, it would be a positive outcome.

But my concern is that students who know they only need to pass a final test to get a good grade will likely think that they can skip the first few months of work and then cram for the big “summative assessment.” They may get lucky and do well, but my hunch is that many will overestimate their abilities and end up doing poorly. “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket” is the applicable aphorism, better heard and appreciated in advance of a disastrous final result.

And for those who do manage to ace the final test, how much of that knowledge will actually stick? An impressive short-term memory may save the day, but will the material enter long-term memory and be retrievable months or years later? The grading may be fairer, but the teaching may fail.

Equitable grading seems inadvertently to promote the cynical view that what matters most in school is acing a few tests in order to demonstrate mastery of key concepts. But the role of testing (standardized or otherwise) is controversial, and I can’t see how those in favor of more equity in grading won’t soon run headlong into those who are vehemently opposed to “teaching to the test.”

And if school simply boiled down to passing a few tests, why even bother with it? Just study for the GED and get your high school degree that way.

Equitable grading seeks to address two important and inconvenient ideas in education: 1.) Students do not all begin at the same place; 2.) Learning occurs at different rates. Evaluating such a variegated student body requires both clear standards and accommodation, but switching from traditional to equitable grading practices only redefines merit, thus picking different winners and losers based on the weighted components selected.

Stay tuned for the next newsletter, which looks beyond grading to what schools should really be focused on: the best ways to study…

[1] https://theconversation.com/every-teacher-grades-differently-which-isnt-fair-201276

[2] https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/19/12/harvard-edcast-grading-equity.

[3] https://takeyoursuccess.com/how-to-figure-out-your-gpa-on-a-weighted-4-0-scale/.

[4] https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/19/12/harvard-edcast-grading-equity.

[5] https://www.nsba.org/ASBJ/2020/February/Accurate-Equitable-Grading.

[6] https://www.wsj.com/articles/schools-are-ditching-homework-deadlines-in-favor-of-equitable-grading-dcef7c3e?st=8bigcnglqrla2cn&reflink=desktopwebshare_permalink

This made me think...While we rightfully have the goals for our children to have bright futures and fulfilling careers in their adulthood, what is the real purpose of an education? Is it to LEARN or to WIN (high scores, top grades, prestige by getting into ivy league schools)?