Taking a step back from the grading wars, it’s essential (and perhaps obvious) to note that doing well in a particular class should be the result of studying—irrespective of whatever grading practices a teacher establishes. If students study well, then, whether they participate in class discussions, do nightly homework, or only ace the final test, they should be learning the material. If they study well, getting a good grade should be the logical result.

Studying is a misunderstood science

But do students study in optimal ways? And are they ever explicitly taught those ways?

On April 20, 2023, University of Virginia professor and psychologist Daniel T. Willingham published an Op-Ed in The New York Times (ostensibly in promotion of his new book Outsmart Your Brain: Why Learning is Hard and How You Can Make It Easy) explaining that students don’t understand the best ways to study.[1]

Infusing the article with examples from surveys of college students, Willingham reveals that the way students go about knowledge- and skill-building is suboptimal. Why? Because they choose methods that are easy and feel good.

For example, students often reread the textbook before a test. After all, that’s where the information came from, so it’s logical to reread and it does feel familiar to review the same pages again. But familiarity does not increase meaning or comprehension. Willingham’s research suggests that students would do better to put their effort into trying to remember what they do know (thereby solidifying the brain’s grasp on it) rather than rereading all the information they don’t know well (a shallow engagement with little long-term benefit). Willingham concludes that activating one’s memory repetitively during the studying process proves to be the best way to make the information stick.

Schools should explicitly teach study skills

Willingham points to what I think is a major flaw in many middle and high schools: they don’t explicitly teach study skills, but schools expect students to pick up how to learn on their own as they engage with what they are being taught. He identifies the essential study skills that are necessary to succeed in school as a “second, unnoticed curriculum: learning how to learn independently.”

From my experience (which is supported by Willingham’s research), many students don’t know how to process, store, and retrieve information. They may be smart, talented, gifted, intelligent, intuitive—or any other number of adjectives we usually use to describe students who do well in school. But they don’t treat studying as a rigorous process, or as a craft, as I like to call it. This is why, when classroom learning flounders, parents call tutors, who, among other subjects, teach the ability to learn how to learn. Tutors put their emphasis on optimizing and personalizing the study process for students—and none at all on grading them.

I believe the academic domain most fraught for students is essay-writing. Schools treat writing as a skill that can be picked up as students read great works of literature or study important historical periods. But historical and literary analysis are challenging skills in their own right, and as the student’s attention goes into comprehending new texts, information, and ideas, the cognitive load fills the brain completely. Asking a student to comprehend a difficult text and also to come up with a personal reaction to the book that leads to a provable claim that the student can support with evidence in a well-structured, proofread essay—that is simply too difficult for many students. Crafting a rigorous writing process takes a lot of time, thought, and self-discipline. (See the work of Natalie Wexler @

for more information about the neuroscience of reading and writing).Besides, writing is a long process, consisting of many discrete steps, each serving its own purpose to achieve a powerful, polished result. Few students intrinsically possess the organization, discipline, and patience to engage with the many steps of the writing process. When students do not succeed in writing to the high standards of their teacher, they are often graded harshly, but they never learn, through step-by-step intervention, what they can do to improve. Composition must be more explicitly taught.

Writing skills are only one element of Willingham’s “unnoticed curriculum.” Taking notes effectively, creating study guides, organizing study groups, planning out information to be committed to memory over a long period of time—these are all crucial to success in school. Other study skills, some of which overlap with a collection of protocols called “executive functioning,” can be taught explicitly and reinforced by teachers who give small, nightly assignments and help students “scaffold” their study processes. I believe that these underlying skills are as important as learning, say, geometry, Spanish, or the ins and outs of the American Revolution.

Grading rubrics should promote good study habits and craft development

Whether grading students traditionally or equitably, the primary goal should be fostering engagement and lowering barriers to entry, providing manageable assignments that help students stay organized and build knowledge and skills.

Traditional grading’s inclusion of class participation as a weighted component of the final grade and its insistence on graded nightly homework reinforce studying as a multifaceted, diachronic process that values more than simply getting the right answer. Keeping students accountable on a daily and weekly basis ideally ensures that students stay on track and, equally as important, learn metacognitively to keep track of their own progress as they develop their study craft. The development and reinforcement of good habits is crucial to helping students understand how the behavior and rhythms of learning feel.

As I mentioned in the last newsletter, the equitable grading movement de-emphasizes nightly work and class participation, putting more stock in summative assessments—in other words, it rewards right answers, not habit formation or good studying behavior. A student may excel in math and do well on a final test without need for nightly repetition; but that same student, lacking study craft, may find himself lost in English class or in history, subjects that are not as intuitive for him. The development of study craft would benefit this student, no matter whether it’s a subject in which he excels or struggles. I worry that, though the equitable grading system may be more forgiving because it considers a student’s family circumstances, it won’t necessarily do much to help the student learn.

Without active class participation (already a problem in traditionally graded classrooms), it will be hard for the teacher to know if students understand new pieces of curriculum. Without mandatory, nightly homework for conceptual and practical reinforcement, the student will never engage deeply or frequently enough to strengthen the synaptic connections her brain is working to build. Without enforced deadlines, students will not learn how to manage their time and organize their studying properly.

Trusting students to work on their own to master material without teaching, and reinforcing, study skills seems a risky proposition. As Willingham shows, students have little understanding of how to study on their own—nor do they understand how memory works, nor how they have to engage their brains repeatedly and in different ways. Teaching students how to engage their entire instrument in the learning process is one of the central tasks of tutoring.

Students who already struggle to keep up with nightly work and participate in class under traditional grading may only fall farther behind under equitable grading conditions. But both grading systems, in offering a single letter or number grade, do little to promote the student’s understanding and development of study skills.

Grading is reductive if it compresses student performance into a single letter

When students receive their graded math tests and essays, they commonly flip to the last page and look for the grade. If it’s an A-level grade, they’re happy. If it’s below that, they’re usually bummed. But crucially, what they don’t do enough is to read through the teacher’s corrections and comments. The grade remains either as their badge or their scarlet letter, a single letter or number encapsulating so many different aspects of learning.

Grading, whether traditional or equitable, is inherently reductive, and therein lies the main problem. How can a letter or a number accurately reflect all the strengths and weaknesses of a particular student? Equitable grading founder Joe Feldman wants to try to weed out all non-academic information from grading, but is that possible—or even desirable?

Let’s take the B+. It’s a maddening grade: solid, but not quite excellent. If a college were to look at a B+ on a transcript, what conclusion would they draw? Would they say, “Hmmm… this student’s academic skills are not quite stellar,” or “This student doesn’t seem to put in enough effort”? Because they’re only looking at a letter (which can’t tell the whole story), how would they ever know that the student didn’t hand in his homework, but aced the final test? Or that he was a frequent participant in classroom discussions, but lost momentum at the end of the semester?

Summative grades of any kind paint an incomplete picture.

Instead of trying to award a composite, final score, teachers should be given more categories that can dynamically reflect all of a student’s abilities, as well as his lapses. What this might mean is that the weighted components that go into the final score can simply stand on their own as distinct categories.

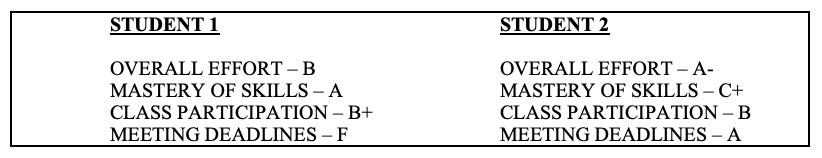

Consider these two B+ profiles if their weighted components were spelled out:

Student 1 happens to be gifted in the subject matter, so much so that by putting in middling effort and missing all deadlines, he manages to master the material pretty well.

Student 2 puts in a lot of effort and meets all deadlines but has poor mastery of the subject matter and doesn’t really engage in class discussions.

Both students end up with a B+ (equivalent to a 3.3 on the 4.0 scale), though they’re totally different people. Their grades should reflect their full profile and not be bundled into a composite score that obscures their individual strengths and weaknesses. Though teachers usually assess student performance in written reports that accompany the grade, college admissions officers rarely, if ever, read them. They’ll only see the B+ (and perhaps a more formally submitted teacher recommendation) and draw whatever conclusions they draw.

But if grading were made more expansive and less reductive, it could help guide students toward better behaviors. A student who does well on tests, but never hands in homework would see an excellent grade for “mastery of skills” and sub-par grades for “effort” and “meeting deadlines.” He might learn how, with small nightly changes, he could perform well across the board. I think a student like that would see how changing his behavior would lift his overall profile in key ways. Many students would likely see that improvements in “mastery of skills” come with increased “class participation” and “overall effort.”

I’m not sure what this “un-reduced” grading system would do to the idea of the GPA as an evaluative metric. Such a system might end up being unwieldy for high school administrators, or too complicated for colleges to process when they evaluate applications, but it might actually provide more useful information on which to base enrollment decisions.

Schools should think more about how grades can be informative, instead of only critical. An expanded grading rubric would highlight to students how they can improve the discrete aspects of their study craft, guiding them to change behaviors and develop new study skills.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/20/opinion/studying-learning-students-teachers-school.html.

This is so helpful! I love examples of a more constructive way of grading!